A couple of years ago, in an effort to improve my chess, I began reading Jeremy Silman’s book The Amateur’s Mind: Turning Chess Misconceptions into Chess Mastery. Silman was a respected US chess coach, author and International Master (he died in 2023). Silman states in the first paragraph of his book

By ‘responsibilities’, Silman means that the chess student must only consider moves that are revealed by the careful examination of the ‘imbalances’ in the position. Examples are:

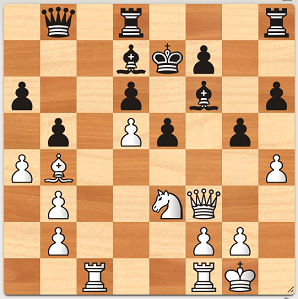

Silman’s idea in the book is to present a position to a number of his pupils, each of whom has a different rating. Silman gives the players a chance to evaluate and comment on the position and then he plays it out against them. He kicks things off by discussion of the bishop versus knight and then presents three of his pupils with the following position:

He warns his students

Silman’s pupils should note these imbalances and use them to guide their play. According to Silman, the main theme of this position should be ‘the bishop-knight imbalance’. The position is from one of Silman’s own games, Silman–Gross in the 1992 American Open and of it Silman remarks

(A class player is defined by the United States Chess Federation as one that has a rating below 2000).

It comes as no suprise then that two of his pupils failed to detect the imbalance and all of them failed to do anything with it. In fact the 1200 and 1600 rated players swapped the bishop for a knight thus obviating the supposed bishop-knight imbalance. As for the 1000 rated player, the whole business was completely over his head. I grappled with Silman’s book and got nowhere with it. The whole concept of assessing a position in terms of the ‘imbalances’ within it was just too abstract for me. I do not have the level of skill that would enable me to make use of such a concept. Fast forward to a couple of months ago and I came across a book provocatively entitled Move First, Think Later: Sense and Nonsense in Improving Your Chess by Dutch IM and chess coach Willy Hendricks, a book that won the 2012 ECF Book of the Year award. In the Preface we are immediately presented with the following position and the statements below it

That looks like the kind of chess I play. This example vividly illustrates the mysterious oversights that can affect the chess player, and in his book Hendricks, inspired by ‘some of the old questions and new insights of the cognitive sciences ...’ . attempts to investigate how the chess player perceives and processes the information contained within the arrangement of pieces upon the squares of the chess board. In other words, he attempts to answer the question “How do chess players think about a position?” Hendricks has definite, and some may say, controversial views, on a common method of teaching players how to think about a position, a method which he believes is totally at odds with the way chess players really think.

He gives an example of a typical exchange between pupil and trainer:

Hendricks maintains that many chess manuals are guilty of using the same pedantic tone that the trainer above is using. The central idea of such books is that you should not try out moves at random but instead take note of the ‘characteristics’ of the position. These will then guide you in the formulation of a general plan of action, and only then can you begin the search for a valid move. Hmm, this rings a bell. Hendricks calls this approach the ‘look and you will see’ doctrine and he dismisses it bluntly as nonsense.

He cites as an example of the ‘look and you will see’ approach a book — yes, you guessed it — Silman's The Amateur’s Mind, and Hendricks reproduces the position from Silman’s book that I showed earlier. For Hendricks, Silman’s approach illustrates “in a nutshell the misconception of the ‘look and you will see’ doctrine.” Authors and trainers who use such an approach, says Hendricks, are forgetting that they themselves do it the other way round:

If this were true, then Silman’s three students mentioned above would have come up with moves that made full use of the bishop-knight imbalance the way Silman himself had done. Hendricks’ point of view is that

Hendricks maintains that there is another, more effective method of approaching a position, a method which is highly despised by traditional didactics. That method is trial and error, and of it Hendricks states

Later in the book Hendricks takes an amusing dig at another teaching technique that he considers to be of dubious value. He terms this ‘the delusion of the verbal protocol’.

Hendricks gives as an example Carsten Hansen’s book Improve your Positional Chess, which he thinks is largely based on this delusion. Of the book he says,

Woolly or what? To illustrate how this ‘advice’ could be put to good use, Hansen then presents a fragment of a game between Alexey Shirov and Garry Kasparov where Kasparov creates a weakness of the light squares in White’s posotion using this ‘goal-oriented play’. Hendricks’ dismisses this as nonsense with a comment that made me chuckle:

And a piece of advice from Hendricks for players who peruse chess books looking for the words of advice that would miraculously enable them to improve their game

Is he talking to me? So we have two opposing views on the best way to answer the question, "what the *** do I move now?". In the blue corner we have Silman and others who promote the use of a generalised, rigid and formal system by which one can identify the characteristics of the position and thus arrive at a sensible choice of move. In the red corner waits Hendricks, tapping his gloves together impatiently and maintaining that an intermediary system that stands between the player and the position on the board is unnecessary and that the players should proceed by investigating the moves that catch the attention and which seem to make sense to them. For my part, I think Hendricks wins the fight. He advocates a way of looking at a position that makes sense to me. It is more natural, more realistic and closer to the way I think than the systematic formality of the ‘look and you will see’ approach. I have found though, that whatever way I think about a position, I still play crap chess.

Move First, Think Later: Sense and Nonsense in Improving Your Chess, published in 2014 by New In Chess.

The book covers much more than the topics I’ve mentioned in this article. It is five hundred pages full of interesting and entertaining material, anecdotes, thought provoking ideas, and even includes a chapter giving advice on how to play the lottery. And it has exercises to boot. It’s a very good read.